Farming

This page will tell you about some interesting things about farming in Bowdoinham's past.

Personal pages from Bowdoinham Advertisers

The snow last week was very good for the new ploughed ground. It's a pity however that we couldn't have had more rain and more land turned over for the snows to land on. B.A. Oct. 24, 1884

There were two huskings in Town last Saturday evening. Owing to the bad weather we were unable to attend, but do understand all had a fine time. B. A. Oct. 24, 1884

The first cucumbers to the PICKLE FACTORY were brought in by Humphery Varney on July 26. Sidney Skelton is now running them in at the rate of a half ton per day. B. A. Aug. 4, 1887

Mr. George Preston recently picked forty-one bushels of apples from one tree. Cider mills are busy grinding up the little yellow and red apples. B.A. Oct. 24, 1884

Pickled

The business for the pickle factory is over for the season, and, notwithstanding the severe frost, the business has been larger in the present season than it was last year. Constable Sutherland reports the receipts to be 62 tons, against 50 tons produced last year. He estimates the damage to cucumbers in this vicinity by the frost to be nearly 20 tons.

Bowdoinham Advertiser

September 28, 1888

Pounding Stray Stock

In 1808, the town voted to build a pound between George Maxwell"s and Nathan Hatch's. The town voted to pay George Maxwell $40.00 t procure the rock and construct the pound; which was to be 25 feet square and six feet tall, with a timber one foot square on the top, and a wood frame gate. The wall was to be three feet thick at the bottom, and one foot thick at the top.

This pound was built and used until about 1885, when it fell into decay and was never used afterwards.

It stood where John Maxwell's barn now stands. (Near the home now owned by Mrs. Lemont.)

Adams History of Bowdoinham, page 234

William D. Curtis killed a pig last week that was just nine months old and weight 444 pounds. If any of our readers have done better than this, we shall be glad to hear from them.

Bowdoinham Advertiser, December 14, 1888

NEED OF A FEW SHEEP

A few sheep are sometimes valuable in wheat growing, and for turning loose in the orchard, where they will not only break up and pack the soil nicely, but destroy weeds and eat up noxious insects. Their manure is also good for the orchard, but is especially adapted to the garden and all hoed crops.

Sheep raising encouragement in all parts of the country, and farmers and farm lands would be inestimably benefited by it. There can be no loss, for early lambs are always marketable, and wool will yield a small profit in any season.

THE BOWDOINHAM NEWS

March 28, 1891

Mrs. H.R. Hinkley sent to Austria some time ago for two queen bees. They arrived a few days ago by mail, in good condition, and ready to do their work. Bees form strange mail matter, and the manner in which they were packed was ingenious.

Bowdoinham Advertiser Aug. 2, 1889

Facts for farmers were articles from different Advertisers

He who by farming would get rich;

Must plough and sow and dig and ditch;

Work hard all day, sleep hard all night,

Save every cent and never get tight.

B. A. April 26, 1886

Keeping the Animals Out of Trees

A good fence, with gates that horses or other beasts can't open, makes the very best protection for trees... but at times it is necessary to plant trees where animals must run for a while. In such cases, each tree must be protected with a barrier of its own. The drawing shows how one Connecticut farmer does it.

He drives down four stout stakes, equally distant from the tree (and far enough away to protect the foliage from foraging). Upon the top of the stakes are nailed four strips, the ends of which project several inches beyond them. A piece of barbed wire is then nailed to the ends of the projecting strips (and probably best put on with a staple) and continues around the tree until the circle is closed.

Another band (or two) of the barbed wire may be put around the stakes lower down, to prevent the animals from reaching below the first circle and gnawing at the trees, and to prevent smaller animals such as sheep, from coming in under the strips.

Our correspondent says the animals soon learn to respect this barrier, and to leave the tree alone.

American Agriculturist, June, 1882

SOAPY MANURE

There is perhaps no better manure than dirty soapsuds; and there is not a farm house in the country but what produces enough of it, in the course of a year, to manure a garden two or three times over.

Dirty suds after washing is almost universally thrown into the nearest gutter, to be washed away and wasted. Would it not be an improvement, and show a laudable economy in the good woman of the farmhouse, to have it conveyed to the garden, to enrich the ground, and make the vegetables grow more luxuriantly?

The potash, the grease and the dirt, all of which are component parts of soapy wash waters, are first-rate manures, and should always be applied to the land to help make plants grow. Especially now, when hard times are largely complained of and sound economy has to be the order of the day.

Brunswicker, June 14, 1843

SHIFTLESS SWINE

The belief that a hog will thrive on any kind of feed, if he has an abundance of it; and the shiftless, reckless ways of feeding practiced by many are the immediate and sole causes of many of the diseases that now prevail among swine.

Bowdoinham Advertiser, March 21, 1890

TO KILL A FOWL

When about to kill a fowl, says a poultry fancier, do not forget that the poor bird undergoes all the terrors incident to such a proceeding, and the work should be done as quickly as possible. It is very cruel to bleed a bird slowly to death.

To properly kill a fowl, first, destroy all hints of consciousness by striking the bird a quick blow to the head with a stick; then use a knife.

Wringing the neck is both barbarous and cruel to the extreme, and anyone so doing should be punished. It is not agreeable to have to kill the birds, but if it must be done, let the work be devoid of cruelty.

Bowdoinham Advertiser, Date not known

These articles were reprinted in the Bowdoinham Advertiser

August 1985

Farmers sweep your chimney and save the sod. You will find there, a very valuable manure for your garden.

The inside of the poultry house should be whitewashed twice a year, or oftener. This practice will keep the vermin away, and leave the hens in better condition.

On a tract which was overrun with briars and brush, a farmer turned 160 sheep. At the time, one cow could not have lived on the whole tract. The sheep were kept there several seasons, and so killed out the wild growth that the tract now affords good pasture for 15 cows.

The sheep were routinely fed elsewhere, and were only occasionally turned onto this waste land, merely to enrich it with their droppings and kill out the unwanted herbage and shrubs . . . fine salt thrown upon the leaves of brush, when the leaves are wet, will induce the sheep to browse them off. In this way, a thick stand of bushes may be killed off in a single year.

Geese are neither profitable nor ornamental; on the contrary, geese are an unmitigated nuisance, befouling grass and water, dooryards and roadsides, and always poking their heads into mischief.

The strongest reason for keeping bees is simply this: Bees afford more clear profit than any other stock kept on the farm.

If the whole day is to be one of exertion, eat very little until the work is done. When the body works, the stomach should rest.

It costs no more to feed good stock than poor, and it is no more expense to handle good manure than poor; hence, care should be taken to keep on the best.

Hardly anything gives a farm a more slovenly appearance than a fringe of bushes around every field, or clumps of bushes and brush growing in the middle of them.

How much more delightful rural life would seem, and how much the drudgery of farming would be lightened, if only the outward appearance of the home were made more attractive.

If you use a steam thrasher, always have a few pails of water on board; in case of fire, they may prevent a serious loss.

It is making use of the little savings that makes the garden pay. Utilize everything when it is at its best.

The great secret of success in gardening is manure and cultivation. Do not hesitate to spend money for good fertilizer.

Advertiser, October 4,1889

PREMIUM FARM FERTILIZER

In the 1860 Sagadahoc County Fair, Bowdoinham farmer George W. Jellison won a first place premium for farm improvement. The Maine State Department of Agriculture Report for that same year goes into more detail about the award.

"Three PREMIUM FARM awards were made in Sagadahoc this year, two of them going to Bowdoinham farmers. It is also a noticeable fact that in all three cases, much attention seems to be given to composting and to the use of marine manures.

"George Jellison of Bowdoinham bought his farm of 120 acres twelve years ago, for $1,600. It then cut an average of 16 ton of upland hay.

"In 1859, he cut 60 ton on forty acres. In 1860, he cut 40 ton of upland, and 16 ton of fresh hay. Value of the crop this year was $1,500."

"The past year, Jellison reclaimed six acres of rough pasture; half of that being a useless alder swamp. He composted the land as follows: 60 wagon loads of swamp muck, 10 loads of thatch hay, 10 cords of rock-weed, to which he added 30 large sturgeons and five hogsheads of fish brine; and finally, the droppings of 20 head of cattle. Another parcel received 7 cords of muck, 10 cords of seaweed, and 6 cords of waste from the pig sty. Both made 'first rate manures,' according to Jellison.

"Other Bowdoinham farmers recognized that year were William White, Bowdoinham Ridge, first premium for underdraining.

J.M. Sandford, Bowdoinham, raising 101 bushels of carrots on one-eighth of an acre.

James F. Mustard, Bowdoinham, for 147 bushels of ear corn per acre.

EGGS. EGGS. EGGS

From Sagadahoc County alone, the fresh eggs exported are 109,600 dozen, worth $15,344. An other 19 tons of poultry, worth $3,800, was sold. In all, the poultry business in Sagadahoc County for 1869 totaled $19,144. It is a business worthy of high attention. Commissioner's Report

State Department of Agriculture, 1860

The farmer who would earn his bread by the sweat of his hired-man's brow had better make up his mind to do without bread. Richmond Bee Nov. 27, 1891

PROPER ROTATION

By practicing a proper rotation of crops and returning to the soil all the manure made from feeding the fodder and the littering with the straw, a farm may be kept increasing in fertility. The soil is really inexhaustible of its mineral matter, and as long as there is decaying organic matter in it there is considerable nitrogen gained from the atmosphere. The longer the rotation, the better and more effective in this way it is.

An excellent rotation, which furnishes feeding and selling crops in abundance, is first clover and grass for hay and then pasture, corn on the turned sod; beans to follow the corn, wheat to follow the beans, and clover sown with the wheat; one year clover; oats on the clover sod, roots on the oat stubble, then potatoes, and wheat following the potatoes with clover and grass to follow and finish the rotation. This requires ten plots, and gives plenty of straw, hay and roots for feeding cattle.

Bowdoinham Advertiser, January 1, 1886

CORN COB FUEL

Do not waste the corn cobs. Use them as fuel and save the ashes, as they contain a very large proportion of potash, and are valuable for that substance alone. In addition, they also make an economical fuel, burning freely and can be collected with very little labor. Bowdoinham Advertiser

March 6, 1885

POSTS ROT

Fence posts resist rot longer if put in the ground upside down. Charring the ends of posts before setting them does little or no good towards preserving them.

MUD HOLE MORTAR

There is no valuable substance about a farm more often wasted in some mudhole than the old mortar of chimneys and lath and plaster walls. This old mortar -the older the better- is a most valuable Fertilizer. It is good upon any soil and upon every crop, used as a surface dressing. It is particularly valuable in garden soil which, not withstanding its richness in nitrogenous manure, sometimes lacks just what it would receive from a dressing of this old mortar.

Teach the Children

Teach your children not to be ashamed of their calling by making it respectable, dignified and honorable as it is useful. Teach them how to help themselves, and they will not then depend on others. Teach them that wisdom makes men humble, and ignorance and pride the reverse. Convince your child by your acts, as well as words, of your love, and they will love, honor and help you.

Fact for Farmers, edited by Sam Robinson, 1869

The Farmers of Keewaydin by Dennis Fiori

T. W. Fisher drag raking hay

Editor's note

This feature about Keewaydin Farm, Fisher Road, and the families which have made its history, was written by Dennis Fiori. He is Associate Director of the Maine Arts and Humanities Commission, and is married to Kathy Jewell, whose parents now own Keewaydin . FDC (April 1977)

The origins of Bowdoinham's Fisher family remain somewhat of a mystery. Some say they moved over from Bath, others say up from Boston, and still others suggest the Fishers came to Bowdoinham from New Brunswick.

What we do know is they arrived late in the 18th century, and it didn't take them long to become an area institution. By the early 1800's Bowdoinham had a Fisher Road, a Fisher tavern, and at least one mill owned by the Fisher family.

We're concerned with the branch descended of John Fisher, a farmer who settled the Fisher Road about a mile from Cathance Landing. Malcolm and Lucille Jewell now live on the place. The present house was built by Thomas William Fisher. He was John Fisher's son, and was a farmer and merchant.

"T.W," as Thomas William is referred to by the family, built his Greek Revival showpiece about 1845, choosing an artificially constructed site formed of gravel and rubble hauled to the site by oxen.

Keewaydin is at least the third house on the site. The earliest house was located in back of the present barn, and the second behind the present house, where the kitchen garden is today. Evidence shows that parts of the first houses were incorporated into the farm of today . . .

In attempting a home like Keewaydin, T.W. must have had aspirations of grandeur pushed by an ambitious wife (Hannah Stinson) who was also a Fisher Road resident.

T.W.'s fortune and aspirations never quite meshed however, and his dream was never quite finished. It wasn't until Dr. Isaac Irish's tenure at Keewaydin that hard floors went in upstairs, and white paint was added to the downstairs woodwork.

Originally, the farm was nearly 80 acres. T.W. raised most of the customary crops and stock, with a sizable field planted to wheat. Before the railroad was finished, T.W. harvested cranberries in the Cathance River lowlands.

In 1845, the farm was bordered by the Cathance River to the east, and roads, now abandoned, to the north and south. The western line was close to the present right-of-way for Interstate 95.

The northern boundary, known as the Booker Road, opened at a tidal inlet on the Cathance called Molasses Creek. The road ran up the hill past the present house, across Fisher Road and then on to Lisbon Falls.

Molasses Creek, now cut off by the railroad landfill, was a docking place for ships whose cargo was often molasses from the West Indies. Vessels were also built on the site. Goods in those early days came off the ships, were loaded onto ox-carts and hauled overland to Lisbon Falls and beyond.

In the 1870's, T.W. and another local man, Elijah Peterson, tried their hands at merchandising, opening a store on the Topsham end of the bridge to Brunswick. They sold a general line of merchandise.

T.W. moved into the Brunswick area, offering the farm for sale, but business was poor and Keewaydin did not sell. After a few years as a merchant, T.W. again returned to life as a farmer.

Three of T.W. 's and Hannah's six children lived&emdash;namely William Otis, Josie and Robert. William Otis was the family adventurer, choosing a life at sea. At the age of 20, he was lost overboard during a homeward passage from California.

Robert was considered the black sheep of the family, and left the area for Augusta and New Bedford, Mass. Josie was a strong willed but vivacious girl, and was eventually to inherit Keewaydin.

Isaac Chase Irish, a Turner native, was one of the last graduates of the Bowdoin Medical School. At Bowdoin he noted that Bowdoinham was doctorless, so he opened a practice here in the early 1880's. To establish his practice, Dr. Irish bought the house now owned by David Steen on Main Street. He divided the house into a duplex and opened his office in what is now the Steens' dining room, to the right of the Main Street entrance.

A few years after Dr. Irish's arrival in Bowdoinham, he married one of the more eligible maids of the village&emdash;Miss Josie Fisher. She was ten years younger than the doctor, and in 1889, the two had their only daughter, naming her Bertha.

Dr. Irish can best be described as a crusty, dry humored and shy Yankee. He was very polite to ladies, and always devoted to his practice. He never failed to go to a patient when called. He was always impeccably dressed, changing from his work clothes to a celluloid collar, starched white shirt, tie, black suit and high Congress boots before he would leave to attend a case.

He was one of the few doctors in the area, his practice covering an area including Bowdoin, Lisbon, Richmond and the Cathance section of Topsham as well as Bowdoinham.

T.W. lived for many years after his daughter's marriage. By 1913 he was in his 90's and still living at Keewaydin, though most of his meals were taken next door at Henry Fisher's tavern. During his last years, T.W. disposed of many pieces of family furniture in exchange for house keeping aid. He remained independent but poor. In 1913 he ended his life with a gun.

Josie, Dr. Irish and Bertha inherited the farm, using it as a summer retreat. Here Dr. Irish indulged his hobby of raising fancy apples on the farm's old terraces. That orchard became a money making proposition with many barrels shipped out of Bowdoinham to England and South America.

Bertha named the farm Keewaydin during this era, drawing from Longfellow's Hiawatha for her inspiration. Dr. Irish made a number of improvements to the old farm about the same time.

Keewaydin became a place for patients to hay and mend fences to pay off debts, and in the summer it was a place for gala parties. The Irishes were quite prominent in town social circles, along with such local gentry as the Randalls, the Coombs and the Kendalls.

Dr. Irish was at the peak of his career at the turn of the century. He was chairman of the local school board, and a leader of the Universalist Church beside his village house. A number of the stained glass windows in that church were donated by him.

Dr. Irish purchased a downtown building for his offices at about this time. He took one half of the second floor for his offices, and rented the other half to a cigar maker. Cigar clippings provided the lice retardant for the Irishes' chicken

The Redmen's Society met in the third floor of Irish's block, and a dry goods store was opened on the street level. Later, the town's post office was in this building, which stands today on the north side of Main Street.

In the fire of 1902, Dr. Irish is well remembered for a statement uttered to save his building. The roof of an adjoining structure was icy this December night, and firefighters were afraid to cross it.

"Doctor, doctor," they reportedly cried. "If we try to cross that roof, we'll fall . . ." and he responded with his usual dry humor, "Keep on pouring boys, keep on pouring, any bones you break tonight I'll set for free." The building survived the blaze unscorched.

Some of the most interesting recollections of the doctor stem from his country travels. He never liked traveling alone, and often carried a collie for company.

One March night before automobiles were available, he answered a call in east Bowdoinham. He tried to cross the ice-locked Cathance from the Bay Road to a place called the Lazy-O, on what is now Wildes Point. It was dark, so the doctor could not see the ice was soft until he was on it. The sleigh and team were swallowed up that night, but Dr. Irish and his collie made it safely to shore.

Dr. Irish was one of the first in town to own a car, and it was not unusual for him to own two. There would often be a touring car for the casual Sunday rides and trips, and a Model-T Ford for his doctoring calls.

It was spring about 1910, that a teacher was needed for the high school, and Dr. Irish was asked to find one. In those days there was the principal and his assistant in the village school; they both taught and administered the whole operation.

Bates graduate John Jewell, of Portland, came over on the train for an interview, and apparently impressed Dr. Irish. The doctor was chairman of the school board, but he took Jewell and drove him out to board member Ned White's on Bowdoinham Ridge for a second opinion.

Dr. Irish and Mr. White interviewed Jewell, and then drove him down to meet the evening train. There on the depot platform, Dr. Irish said, "Well, I don't think we can use this young man, do you Ned?" The next day Jewell was hired. Ten years later, the principal married the board chairman' s daughter .

Bertha Irish Jewell was a very bright young lady. She attended classes at Bowdoin College back when educated women were frowned upon, and her skill as a teacher of piano was second to few in the area.

She inherited her father's penchant for machines, took up photography as a hobby and science, and in her spare time, would record the actions and habits of birds out in Bibber's woods.

Many of her photographs remain to document the town at the turn of this century. She even experimented for a time with double exposures on negatives, trying with some success to develop ghost-like or supernatural images.

Her careful record of bird observations around 1910 still exist, and could serve as models for observers of today.

John and Bertha left Bowdoinham in the early 1920's for Massachusetts, where John commenced a teaching career that would span 15 years. During those years, however, there were frequent and extended trips to town for vacations at the farm on Fisher Road. Elizabeth Jewell was born at Keewaydin during one such stay, delivered by our own Dr. Irish.

Malcolm would be born away from Keewaydin, but his ties to the farm would develop early, and they would prove to be permanent.

Dr. Irish died in 1937 at the age of 84. His widow Josie remained with the village house, and Keewaydin again became a summer retreat. In 1946, Malcolm left the Navy and opened Keewaydin with his wife Lucille and their growing family. Since that day, Keewaydin has been what it was always intended to be . . . "The best darn farm on the Fisher Road."

Bowdoinham Advertiser, July 1977

Frank Connors, Editor

Farmer's Notes

RAISING GOOD RADISHES - Take pure sand, dug up some depth from the surface; or some pure earth, taken from below where it has been normally tilled or moved; or gather sea sand, which has been washed by the waves. Make a bed in the garden six or eight inches deep, and as big as you please. In this land, sow your radish seed and they will be free of worms and will grow well without a manure.

Radishes that are grown too early in the spring are of slow growth and are inferior to those grown after the weather is warm enough to hasten them along. The faster a radish is allowed to grow, the more tender it will be, and the finer flavor it will have. Brunswicker, June 15, 1843

GETTING THE YELLOW BUG - In every hill of cucumbers, squashes, and melons, set out one or two old onions! This is said to be an infallible remedy for control of the yellow bug. Try it!

Planting on newly plowed pasture lands, and manuring with dung from the hog cote will guarantee a certain crop. Try this too! Brunswicker, April 25, 1844

GROWING EARLY PEAS - The pea vegetables at a very low temperature and is wholly unaffected by frost or snow. If the ground was plowed last autumn, you may safely sow as soon as there is a sufficiency of soil free of frost to cover them.

Spread old, well rotted manure on the surface, and to this add a sprinkling of plaster of Paris, ashes, or carbonate of lime. The dung will absorb the heat and will cause a more steady germination. At the same time, it will also prove highly beneficial to the youthful plants as well as the soil. Peas cultivated in this manner will be fit and full for the market in June, where as the same variety raised in the ordinary manner will scarcely acquire maturity before July. Brunswicker,May 11, 1843

SOAP SUDS - There is no better manure than dirty soap suds; and there is not a farm house in the country that doesn't produce enough dish water in the course of a year, to manure a garden two or three times over.

Dirty suds after washing is almost universally thrown into the nearest gutter, to be washed away and wasted. Would it not be an improvement, and show a laudable economy in the good woman of the farm to enrich the ground and to make the vegetables grow more luxuriantly?

The potash, the grease and the dirt, all of which are components of soapy waters, are first rate manures, and should always be applied to the ground carefully to help plants grow. Brunswicker,June 15, 1843

PRESERVlNG EGGS - As the season of fresh eggs will soon be over, perhaps some of our readers may want to know how to preserve some for fall and winter use.

Take new laid eggs and rub them over gently with lard or butter. Pack them in a box or keg, with their small ends downwards, and then set them in a cool place. The grease stops the pores of the shell, and thus excludes the air; and by resting on the small end, the yolk is prevented from reaching the shell and spoiling.

An older, but not so effectual a method of preserving eggs is to pack them, small end downwards, in layers of salt, and keep them in a cool, dry cellar. Brunswicker,July 20, 1843

KEEPING POTATOES FIRM - Kiln dried sand will keep Roxbury Russets perfect for a year. Bury the potatoes completely in the dried sand, then store them, sand and all in a dry place. Cathance Breeze, June 4, 1876

EDITORS NOTE: The BRUNSWICKER was a weekly literary newspaper printed in Brunswick in the 1840's. These excerpts come to the ADVERTISER, courtesy of the Pejepscot Historical Society, Brunswick. F.D.C.

Bowdoinham Advertiser Vol 2 #3

A Hill Farm Huskin'

Copied with editing from Richmond Bee, January 24, 1890

Charles Hill, who lives down near the Kennebec River, is a prosperous farmer whose cornfields have been unusually productive this year. When he viewed the overburdened shocks of corn a few days ago, and thought what a tough job it would be to husk and store it in ears, he felt depressed.

He spoke of this problem to his wife, and Mrs. Hill's quick wit came to the rescue. "Let's give a husking bee," she suggested, and the husband at once fell in with the idea. Invitations were sent out to all the boys and girls in the neighborhood, and there was a very favorable response.

When the night came, the barn floor had been thoroughly swept, clean straw had been laid down in a circle big enough to accommodate 60 persons sitting Turk-fashion, and in the center were Hill's many shocks of corn.

The barn was lighted with many lanterns, back of which bright new sheets of tin had been nailed to the posts. The stalls in which Mr. Hill kept his cows and horses faced toward the center, and the meek-eyed cattle stuck their noses over the mangers, and chewed their cuds contemplatively.

At eight o'clock, the company was seated around the cornstalks, and Mr. Hill, mounting a box, laid out the one single rule. The first red ear of corn found by a young man entitled him to kiss any or all of the pretty girls assembled. The second red ear gave the privilege of kissing only a certain number of the beauties, and the third red ear offered still a smaller number, and so on.

The same rule applied to the girls, if they cared to indulge.

Once the husking began, it was half an hour before the first red ear came to view, and it was an East Bowdoinham youth who found it. Mr. Hill had been wise, seeing that the proper amount of work was finished before the merriment started.

The first intimation that any of the company had that a red ear had been found was a sudden sweep of the arms around the girl next to him, and a resounding smack of the lips. Then he held up the ear and collected the other forfeits. That is, he tried to, but there was more solid work for him in the next half hour than he had ever done in a day before, and there was no corn huskin' done in that time, either.

The girls screamed and giggled, then ran, with the lucky East Bowdoinham youth hot on their heels. It was such fun that even the cows laughed. This happy scene was repeated when the second ear was found, and again when the third was located and husked. The fourth, fifth, and sixth red ears came, but by then, the girls were giving up and submitting with better grace.

After the corn was husked to the last ear, the floor space was cleared again and the fiddler tuned up his strings and began to grind out "Money Musk" with such feeling that every foot in the place was keeping time.

It was one of the jolliest, happiest, heartiest dances the Hills ever saw. During an interval supper was announced, and all enjoyed the baked beans, boiled ham, cold roast turkey and chicken, then cake and mince pie, all washed down with fresh cider.

It was a profitable party for Mr. Hill. He got his corn husked for the cost of the supper, and few of his guests even noticed the labor. Above all, Mr. Hill is today being called the most popular farmer in this part of Sagadahoc County.

Bowdoinham Advertiser, February 1982

Frank Connors, Editor

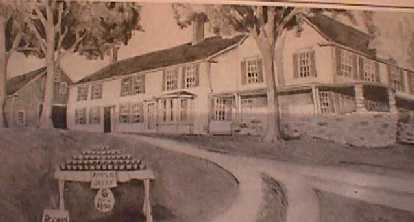

Jelly by the Side of the Road

The Nealey-Sewell farm (drawing by Sarah Stapler)

Ohio librarian Willis Fuller Sewall bought the Nealey farm and its apple orchards on the Post Road about 1915, planning to retire here and become a country gentleman farmer. In those early days, Sewall probably thought of jelly only as he buttered his breakfast toast.

It was Dora Billings Sewall who marketed the first Federal Road Jelly, and she started in the business quite by accident. All those fruit trees on the farm produced a surplus apple crop most years, and Mrs. Sewall developed the habit of putting baskets of apples down by the road, hoping to sell them to passing travelers. More often than not, however, evening would come and most of her apples would still be there, and someone would have to tote them back up the hill to the apple barn.

Dora Sewall was making a batch of crab apple jelly one day, and on a whim, took a few of the glasses down to the road and placed them atop her apples. She reasoned that people could see first hand what fine jelly her apples would make, then they might be a bit more willing to buy a bushel or two.

Mrs. Sewall didn't have long to wait. Just minutes after placing the preserves down at the road, there came footsteps on the porch, and a knock on her door. A dapper looking man stood there, holding a dollar in one hand, and her four jars of jelly in the other. He said he wasn't really interested in the apples, but he would consider it a bargain if he could swap his dollar for the preserves.

Mrs. Sewall nodded her head, and the Sewall jelly business was off down the road to sweet success. Before it would all end, this homespun industry would gain New England wide fame, and would produce up to 26,000 jars of jelly per year.

The time-tested and tasty recipe was Dora Sewall's own; developed carefully through her own experience by reading farm bureau handouts, and by comparing her note with those of other kitchen-jelly cookers in town.

Before the recipe was perfected for mass production, the Sewalls learned&emdash;the hard way&emdash;there were pitfalls to the cooking jelly. They learned that great care had to taken during all phases of the jelly-making process; if not, the final product would be drastically affected.

THE RECIPE

The apples were cut into sections, peels and all, using a french-fried potato cutter. After slicing, the apple sections were placed in large, white-enameled stock pot, large enough to hold a half bushel of the shredded apples and a full bucket of water. During an average "cooking," the Sewall jelly makers would have eleven of these half-bushel kettles boiling one time.

With the kettle three-quarters full of sliced apples, water was poured over all until the apples floated free of the kettle bottom. The apple-water mixture was then heated quickly on a very hot fire until the contents boiled then the heat was lowered so the fruit would cook completely, separating the juice from apple pulp.

When all was set for straining, the hot apple stock was poured into a fruit press lined with a cotton-flannel bag, then pressure was applied until all the juice was forced through.

The juice, less the pulp, was then strained a second time, through a clean, cotton-flannel sieve tied across the top of a kettle. During the second straining, great care had to be taken not to force any of the residue through the flannel. If pressure was applied during the second straining, the preserve would not jell perfectly clear.

When the juice was ready for condensing, only eight cups of the liquid were worked at a time. The Sewalls knew that smaller quantities made better quality.

The boiling was done on an intense flame, again using a white-enameled pan. The juice was allowed to boil away about half of its original volume before any sugar was added.

The bubbles told an important story during the boiling. Large, rolling bubbles worked up through the liquid as condensation started, but only small, lazy-rising bubbles were seen when the syrup was ready for sugar.

For the eight-cup batch of juice (as measured before the condensing), Mrs. Sewall added about four cups of sugar; her rule varied slightly with the type of apple used. She found that crab apples needed nearly five cups of sweetener, while Starks, Spys, Macs and Cortlands made fine jelly with 3 1/2 to 3 3/4 Cups of sugar.

To be sure of what she was doing, Mrs. Sewall would work up her first pan using 3 3/4 cups of sugar, adding more sugar as needed, if needed. If the jelly was too sweet, she would thin it by adding a little more hot apple syrup.

The Sewalls used a tablespoon to test their jelly when nearly done. The spoon was dipped into the hot syrup, lifted a few inches out of the pan, and then dropped back. When separate drops clung at the bottom of the spoon, it was nearly boiled. When instead of droplets, a sheet formed on the edge of the spoon, stretched a half inch or more and then broke loose at one end, the jelly was ready for jelling.

During the first two years of their jelly business, the Sewalls sealed their jars with wax. That is, they filled jars nearly full with the hot syrup, then melted wax was poured over the top, effectively sealing the glass against spoilage. In the third year of operation, the Sewalls added a machine sealer to their operation, doing away with the sometimes messy wax.

During their first year, the Sewalls produced 5,280 glasses of jelly, and the annual output increased steadily until at their peak, they were selling 26,000 glasses per year.

Much of the selling was done right at their Post Road home, either through a mail order service the Sewalls developed, or to the countless travelers who saw the sign by the side of the road, or knew of the jelly through reputation. The Sewalls also did a brisk business by attending and selling at agricultural fairs. As an example, during one week at the Eastern States Farmer's Exposition in Mass, they sold more than 3,000 jars of jelly!

The jelly business became a full-time, year round job for Mrs. Sewall. Jelly-making started in early fall with the pre-season apples, and continued right through fall and winter. April would pass on the calendar before the last of the winter-keeping Ben Davises were gone, and the Sewalls could take off a few months from cooking.

Mrs. Sewall is now remarried, and living in Carmel, Maine. She recalls the years when she made and sold jelly on Bowdoinham's Post Road. "I'll never be able to forget them," she says with a smile. "Those days took away any taste I ever had for jelly . . . to this day, I can't stand the stuff."

Bowdoinham Advertiser, February 1977

Frank Connors, Editor

KENDALL'S DANDY DIGGER

Few people know when eating potatoes that they have had to be hand-picked from the ground. Including all those potatoes raised in the United States, 10,000,000 tons per year have had to be harvested in this manner.

We have had a wheat harvester, a corn harvester- every appliance for agricultural harvesting, it seems, except a potato machine. The reason for this lies in the fact that most other agricultural products are on the top of the ground, while to harvest a ton of potatoes, a farmer is obliged to also handle five tones of dirt, rocks and vines.

Now however, E.P. KENDALL of Bowdoinham, Maine, has conceived the idea of a potato digger with a very large capacity, one that is much longer, and much wider, than any of the harvesters that have been failures in years past. His machine, shown in the accompanying illustration, has finally solved the problems of harvesting potatoes.

Kendall's harvester works by running the large elevator chain on which the potatoes are moved, driving this chain very slowly-and therefore requiring very little power-having this chain rise or fall onto springs and by keeping the chain in operator controlled agitation at all times.

After leaving the potato digger, what is left of the dirt, rocks, vines and potatoes is caught up by a smaller machine that trails the digger, called the harvester. This is simple in nature, consisting merely of an endless chain of buckets, in motion all the time that the digging machine is being run.

These buckets, being on an inclining plane, separate the potatoes from the remaining vines and dirt, and carry them to the top of the elevator. There the lower edge of the bucket drops, allowing the potatoes to drop also, but the vines and the waste matter continue over the end of the elevator, and are deposited beyond, on the ground.

The potatoes, falling onto a cross belt at an angle of 45 degrees, immediately begin to roll, jumping across an open space of several inches. All dirt, rocks or vine matter remain stationary and pass through the open space that the potatoes have leaped, making it impossible to get any vines or dirt into the bags or barrel.

The Kendall digger has passed the experimental stage; it stands ready to demonstrate to any doubter that it can dig, separate, and bag five bushels of potatoes during each minute of its operation. The Kendall digger can reduce the cost of potato harvesting from $7.00 down to $2.00 per acre, perhaps even more in a large-scale farm operation.

Editor's note: This article is a reprint of an old news paper clipping given to the Historical Society by Mrs. Phillip Moone. It was originally published in "Illustrated World." We don't know the date. Any person knowing the whereabouts of one of Kendall's "Wonderful" diggers should contact the Historical Society immediately. We'll want to photo graph it.

FDC

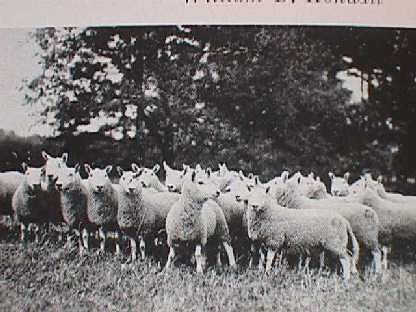

SHEEP

Editor's Note: In 1921, Maine was feeling the effects of a declining agricultural base, and Bowdoinham's W.B. Kendall was in the forefront of those trying to beat the trend. His,Long Branch Sheep Farm was fighting for survival, and he consented to this interview with the Lewiston Daily Sun as part of his "missionary work." The message is still there, even though Kendall is gone. FDC

BOWDOINHAM HAS become known for the sheep industry being carried on by the Hon. William B. Kendall. At one time, it has been said, Mr. Kendall had the largest flock of sheep this side of the Mississippi River.

The existing conditions of the past two years have been the cause of reducing his flock down to about 400 at the present time, Cheviots being the principal breed retained. The weeding out process is not yet completed, as plans are being made to turn over even more of the flock. "With conditions as they are," said Mr. Kendall, "the sheep industry has had to suffer with everyone else."

George Weeks of Canaan, a practical sheep man, is the present superintendent of the Long Branch farm. Like the proprietor of the place, he has great faith in the Cheviot for Maine. That they possess many splendid qualities in the opinion of both these men.

Mr. Kendall says that with ten years experience in breeding and raising sheep of the Cheviot line, he is fully convinced that they are adapted particularly to our climate. IF all others are eliminated, he says the Cheviots will always be retained at Long Branch.

"A home consumption of wool is the only hope of maintaining the sheep industry in our state," says Mr. Kendall. "Wool is down flat in the market place, which has discouraged the sheep men and many others who could have entered the business. Many of those who have just started in the business have gone right out again. It seems like survival of the fittest, just the way it is with the dairymen. Cattle are also very low in price," Kendall,said, "and many of the stockmen are getting discouraged."

"However," he added, "I shall have to be harder pressed than I am now to go out of the sheep business. In fact, I believe today there are opportunities for a person who likes sheep and is willing to start a flock. With the increasing diminishing of sheep in New England, it will make lamb higher and, after the readjustment of things is fully made, I have faith that wool will go up again."

"A sheep can tell quite a story," Kendall said. "If she could talk, she would say in the spring, I have a heavy coat of wool I want you to take off. Then I want you to turn me out on one of the hillsides with my twin lambs. During the summer, I will grow you another fleece of wool, and my lambs will grow and make good meat or stock for breeding purposes. All summer long, we will eat the grass and weeds in that old pasture and enrich the soil at the same time. You will not have to take any care of me, as you will be busy with your crops. Just bring us some salt and tobacco each week, and we will be alright, all summer long. If you want to you can take your family and go away for two or three weeks. At the same time, we will be working right along, every day, producing for you. What other branch of the stock industry can do more for you?"

"There is every reason to believe," Mr. Kendall continued, "that the people themselves are more or less responsible for the great decline in sheep. The man who rides over our great state in an automobile and sees nothing in our hillside pastures, when they could be filled with sheep, is in great measure to blame."

"He just doesn't seem to care," Kendall said, "He is not a good patron to the welfare of our state. He'd just as soon buy his woolen goods from the west, and go without native lamb or mutton. Just suppose for a moment, that every person in this state spent only ten dollars each year for Maine-made woolen goods. Do you realize that investment would equal $750,000?"

"There is now being gotten out some very good cloth, blankets and clothing from our wool," Kendall said. "This kind of a market will help us retain the sheep husbandry, as it makes a better market for our wool. If the people will only do their part, much of the waste lands in this state can be utilized to good advantage, and turned into something in the productive line."

"The whole story is this," Kendall concluded, "farming-has got to be woven into a tighter web. It makes a great difference whether a man can take care of the flock himself, or has to hire it done by paying a man three or four dollars a day. The various branches of a farm are all looms working together. The closer one can conduct his factory, the better he will be."

Bowdoinham Advertiser, August 1980

Frank Connors, Editor